Consultant , Oakwood International Security

The publication of Global Britain in a Competitive Age: An Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (16 March 2021) sets forth the Government’s analysis of and agenda for security until 2030. In a series of articles analysts at Oakwood International Security examine key aspects of the Integrated Review and the accompanying Defence Command Paper (22 March 2021). In the third article within the series, Roger Darby looks at the implications for Human Resource Management in defence.

Analysis of the global defence and security sector in the British Government’s recent Integrated Security Review and Defence Command Paper highlighted the central tenet of change. Namely, the status quo is no longer acceptable, desirable, or realistic. Stating it more bluntly, Britain’s military capability cannot stand still. Although change is a constant, however, it is important to stress that change is not consistent. For example, the security professional of the future will look very different from the security professional of today.

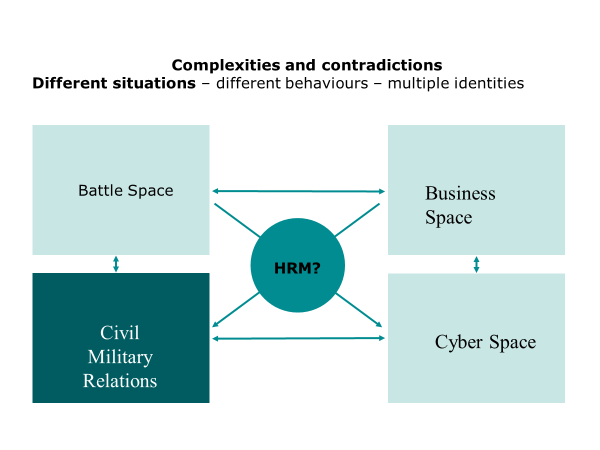

The recent publication of the Integrated Review of Security and the Defence Command Paper also focused attention on the UK MOD’s requirement to address the quantity v. quality conundrum. Traditionally, quantity, or mass in military parlance, has been viewed as a critical enabler in the attainment of effect. In the past, human resource planning was mainly about determining size (quantity). However, the nature of the risks the UK faces now and in the future means that scale will be less important than capability. As identified in the Defence Command Paper, emphasis has demonstrably shifted on the need to focus more on a qualitative approach. HRM (human resource management) strategies will need to enable reduced permanent forces to carry out more diverse tasks, ones that will only emerge in the future. This in turn requires a more flexible workforce with transferable skills ready to meet the needs of the different defence ‘spaces’ including operating in a so-called ‘grey zone’ between peace and war. This presents changing requirements in a multiplicity of locations and diverse and often, contradictory environments, as highlighted in the diagram below.

An intriguing backdrop to the recent review is the question of whether the tempo and persistent global engagement will seriously challenge the UK’s armed forces capability in the different spaces, in the future. For example, light, high-tech and globally deployed troops lie at the heart of this Command Paper, however, a lighter, more agile, and more global army also has more weaknesses, for example, in combat support. The British government has acknowledged it will need to augment reduced personnel numbers through continuous investment in ships, submarines, combat aircraft, new technology, and unmanned platforms if they are to counter successfully the unprecedented challenges of cyber security and prepare for conflicts wholly unlike those in the past 20 years. Consequently, increased demands for more skilled security personnel will include for example, cyber-soldiers, satellite controllers and software engineers. A cohort of personnel that are already at a premium in the wider competitive labour market.

From an HRM perspective, three issues raise concerns. First, the central role of human capital needs to be acknowledged more fully in strategic reviews and defence plans. That includes identifying the correct ‘quantity’ of personnel (juxtaposing a planned decrease in the number of permanent staff with an increase in the number of reservists) to suit a multiplicity of spaces and situational contexts. Indeed, General Sir Nick Carter, Chief of the Defence Staff, noted in the Defence Paper that army strength will be reduced from 82,500 to 72,500 troops (the smallest size since 1714). This is contrasted with an increase to 30,000 reserve troops with 6 months readiness who will be made available and added to the overall numbers.

Second, there is a long-term requirement for HR strategic planning and resourcing to ensure the availability of ‘quality’ staff with the necessary skills, knowledge, and experience to be flexible and agile enough to meet the changing requirements within short, medium, and long-term time frames. History has not been kind in this area of defence management, with old habits still prevalent and witnessed in poor strategic HR management. Some commentators would argue that the same is true in defence procurement and acquisition.

Third, there is the ubiquitous issue of timing – cuts naturally create personnel gaps exacerbating knowledge gaps which can linger unfilled for many years. Take for example the Navy, which will have to shrink before it can grow to its larger planned size. In procurement terms, one can also see there is often a ‘knowledge gap’ between the business and the security service when buying new equipment.

It is contended in this article that the UK MOD needs to be more professional in coming to terms with the concept of HRM, and not before time. This connotes a change of mindset in institutions that will acknowledge that people are a key asset; whilst also recognising the need for employee engagement to ensure staff are managed more effectively, efficiently and economically. Consequently, relevant, updated HR management and leadership skills are of paramount importance for the modernisation of defence and security forces. The demand for more relevant, updated HR management and leadership capability has occurred in many Forces around the world where defence budgets have fluctuated but demand for security services has remained constant if more complex. The reality is that the British Armed Forces, similar to many others across the globe, will experience rationalization, restructuring and increasing complexity in all of the operating spaces.

As in all sectors, Defence faces an uncertain future. That uncertainty will inevitably affect key management practices like HRM. Various critical questions about human capital requirements, suitably trained staff and financial cost will continue to emerge in parallel with future national and international challenges to the country’s economic, social, political, cyber and security environments.

The over-arching theme in this article has been that ‘people’ are the most important asset in any organisation. To-date, however, they have been the most expensive and the most poorly managed asset. To continue the cycle of waste and misuse of talent will be seen as an example of bad management practice. No organisation, including the UK MOD can afford this perception if it wishes to maintain its capability and sustainability in the future and remain relevant in a fast-changing, complex, and uncertain global security environment.

For too long the armed forces in the UK have been driven by over-ambition and over-spending from governments unwilling to be honest about the cost of defence. The latest Secretary of State for Defence, Ben Wallace, purportedly began his major review by telling officials to do away with spreadsheets and focus on the ‘threat’. To counter the threat requires resources, however, and this defence paper is evasive on many details – including the size and timing of investments. While commentators have suggested the Defence Command Paper is bold and visionary, it remains to be seen whether it will be properly funded….and, more crucially, the armed forces appropriately staffed, for an uncertain future.